“Fine For You, But Not For Me”

In late 2017 a Long Island based lemonade and iced tea corporation called ‘Long Island Iced Tea Corp’, decided to change its name to “Long Island Blockchain Corp.” Later that same day its stock price shot up over 200 percent. You probably won’t be drinking blockchain-based ice tea any time soon (or torrenting lemonade for […]

In late 2017 a Long Island based lemonade and iced tea corporation called ‘Long Island Iced Tea Corp’, decided to change its name to “Long Island Blockchain Corp.” Later that same day its stock price shot up over 200 percent.

You probably won’t be drinking blockchain-based ice tea any time soon (or torrenting lemonade for that matter), but it is clear that a dip into the lexicon of decentralization can be enough to fatten one’s pockets. If you can back up that chatter with some genuinely interesting output you might be able to make something that really matters. It is surely an exciting time to be a dweeb.

Decentralization — the guiding principle of peer to peer technologies like blockchain — seeks to disperse concentrations of power, breaking apart hierarchies and allowing the fragments to form connections one another and manage themselves, eliminating the need for monolithic mediators. Or so that’s what I’ve heard. Decentralization allowed Napster, for example, to bring the entire music industry to its knees by allowing the masses to share music for free. Communication protocol companies such as goTenna (*wink wink*[Winks and other implied gestures are those of the author and do not reflect the ocular contractions of In The Mesh – Editor.]) have created a new route for message relay, and currencies with the suffix “coin” have certainly provided an interesting means for people to transact.

Well guys, gals, and nonbinary pals, while I’ve got you here let’s consider the potential to decentralize another social institution: private property.

For the purposes of this conversation it will be helpful to clarify what I mean by private property. Generally, I’m referring to land and natural resources.

A great many proponents of decentralization would balk at the idea of curtailing something so given, so natural, so self-evidentiary. But private property (or property in general) is a triadic social relationship between you (or an institution), an object (or thing) and an enforcer. Are such hierarchies self-justifying? Let’s see.

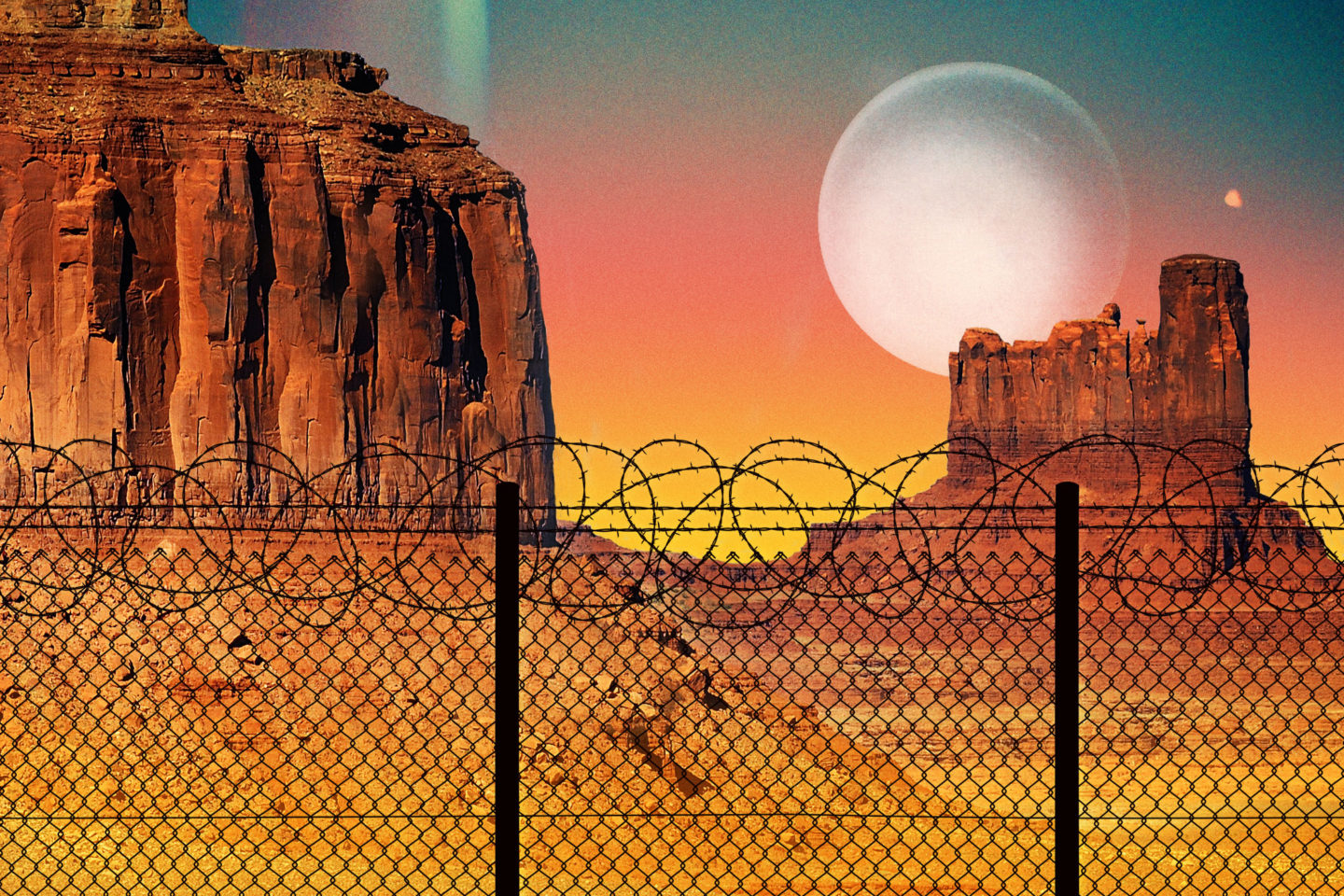

Imagine you are in an open field. There is one other person with you in the field, and both of you walk back and forth across the field — likely wondering why you’re trapped in this strange field-based thought experiment. Your field-mate decides one day to get some chalk and draw a circle on the ground, telling you that, should you step into that circle, an institution they’ve been in communication with will exact severe and merciless punishment. Without asking you, this person expands that circle wider and wider, limiting the space available to you and eating away at what political theorists might call your “negative liberty.” It makes no difference whether your weirdly territorial field-friend refers to themselves as the “state” or as a “private security agency.” Does it not still seem coercive — at the very least — to be left without a meaningful choice?

Now imagine that they built a fence around an area and told you that the “state” or “private security agency” would kick you in the balls if you stepped into there, their reasoning being that there are opportunities within that they’d like to take advantage of. Maybe the fenced area contains the only arable land in the whole field. Clearly, you need access to the fenced area or you will starve (even hypothetical people need to eat!)

The main argument here is that there is nothing given about this hierarchy. It’s an arbitrary product of the social relationship that obtains between you, the other person, and the institution that sides with him. It’s strange to describe this arrangement as a “right.” How many “rights” do you know of that operate by excluding others from the opportunity to exercise their own? When an institution arbitrarily privileges the benefit of the few over the needs of the many, it creates an imbalance that does violence to the whole of society. Property is one such institution, and the way to restore balance to it is by decentralizing.

Is property in fact centralized? It is, by necessity. In most societies the government holds a monopoly on force and reserves the right to act as sole enforcer in property disputes. Without centralization it is unlikely that an ambulance or conga line could efficiently pass through multiple regions without friction.

The problem is that state power is not evenly distributed; it favors those who already have capital (assets), allowing them to accumulate more land and resources over time. This is why those who have found themselves on the receiving end of the state’s monopoly on force (sometimes for reasons wholly outside of their control, and sometimes for generations) are not only placed at an immediate disadvantage, they are embedded within a system that cements disadvantage in place indefinitely. To describe this as “equal opportunity,” is… maybe overselling it a bit?

If this sounds far-fetched, consider the case of the United Fruit Company. In the early- to mid- twentieth century, the United Fruit Company owned sizable tracts of land throughout Latin America, which gave them huge influence over the local governments. By centralizing ownership of the land and critical infrastructure, the UFCO was able to dominate local economies and coerce people into working on the same lands they had farmed for hundreds of years before the Boston-based company began importing bananas to the United States. When the people balked at this arrangement and went on strike, the UFCO was quick to appeal to state enforcers (as they did in the famous Banana Massacre in Colombia, and the Guatemalan coup of 1954.) All this over some profitable potassium.

Decentralizing property does not need to be some radical act. Some of the world’s most successful social democracies already practice some form of property decentralization. Freedom to Roam laws, also referred to as Right to Roam laws, also referred to as Pure Weakling Entitlements (I made that last one up), are prevalent in the Nordic countries and surrounding regions. For private property deemed too vast, or limiting the public from experiencing beautiful regions considered socially desirable, they can be partially accessed used by the public, exercised on, hiked on, cried on (my specialty) etc. This is a compromise that maintains the property rights of landowners without eliminating opportunities for the public to use that land.

Intellectual property is another area ripe for decentralization. One way to keep the benefits of exclusion and simultaneously limit the enclosure of thought would be to limit the term of patents, implement a company size tier for copyright — i.e larger companies have a harder time exercising intellectual property, etc. The goal here, again, is decentralization and dispersal of power.

There are many other ways we could effectively redistribute private property without going full-Bolshevik. In the United States, the tax code could be streamlined in a number of ways. A more progressive tax, such as this country had during the New Deal, would simply tax those with higher incomes at a higher rate than those with lower incomes, redistributing resources from the propertied to the dispossessed. An increased of the marginal tax rate on capital gains (i.e any income you could unknowingly earn while being in a coma) or inheritance (money income earned when its owner is no longer in a coma) would both be ways of making non-productive resources available to a greater number of people, and would sustain larger, more resilient markets from the ground up.

The concept of Employer of Last Resort (also called a Jobs Guarantee) is the basic idea that everyone in society who is able to work should be given the opportunity to do so. One of the contradictions of a system in which property is highly centralized is the requirement that everyone spend so much energy and resources acquiring property can leave many important tasks un-done. Unused resources, fallow land, capital capital kept out of circulation, underutilized labor could all be marshaled for the public benefit. If a sovereign government demands taxes in a currency it issues, then here it provides a means for everyone to earn that currency.

UBI, or Universal Basic Income. UBI is simple, is another policy proposal that is gaining traction from all across the political spectrum. The idea is simple in principle — just give everyone money. This is perhaps the most straightforward way of decentralizing wealth (and its attendant power); every person gets a set amount of money to spend however they see fit. A major benefit of UBI would be to liberate workers from the coercion they experience as a result of not owning property.

As Noam Chomsky once said in a 1996 Harvard speech on real world capitalism, critiquing the attitudes of some of its most powerful participants, “free markets are fine for you, but not for me.” Ultimately decentralizing property would lead to greater competition among those with capital, at the benefit of reduced competition for the rest of us.

In late 2017 a Long Island based lemonade and iced tea corporation called ‘Long Island Iced Tea Corp’, decided to change its name to “Long Island Blockchain Corp.” Later that same day its stock price shot up over 200 percent.

You probably won’t be drinking blockchain-based ice tea any time soon (or torrenting lemonade for that matter), but it is clear that a dip into the lexicon of decentralization can be enough to fatten one’s pockets. If you can back up that chatter with some genuinely interesting output you might be able to make something that really matters. It is surely an exciting time to be a dweeb.

Decentralization — the guiding principle of peer to peer technologies like blockchain — seeks to disperse concentrations of power, breaking apart hierarchies and allowing the fragments to form connections one another and manage themselves, eliminating the need for monolithic mediators. Or so that’s what I’ve heard. Decentralization allowed Napster, for example, to bring the entire music industry to its knees by allowing the masses to share music for free. Communication protocol companies such as goTenna (*wink wink*[Winks and other implied gestures are those of the author and do not reflect the ocular contractions of In The Mesh – Editor.]) have created a new route for message relay, and currencies with the suffix “coin” have certainly provided an interesting means for people to transact.

Well guys, gals, and nonbinary pals, while I’ve got you here let’s consider the potential to decentralize another social institution: private property.

For the purposes of this conversation it will be helpful to clarify what I mean by private property. Generally, I’m referring to land and natural resources.

A great many proponents of decentralization would balk at the idea of curtailing something so given, so natural, so self-evidentiary. But private property (or property in general) is a triadic social relationship between you (or an institution), an object (or thing) and an enforcer. Are such hierarchies self-justifying? Let’s see.

Imagine you are in an open field. There is one other person with you in the field, and both of you walk back and forth across the field — likely wondering why you’re trapped in this strange field-based thought experiment. Your field-mate decides one day to get some chalk and draw a circle on the ground, telling you that, should you step into that circle, an institution they’ve been in communication with will exact severe and merciless punishment. Without asking you, this person expands that circle wider and wider, limiting the space available to you and eating away at what political theorists might call your “negative liberty.” It makes no difference whether your weirdly territorial field-friend refers to themselves as the “state” or as a “private security agency.” Does it not still seem coercive — at the very least — to be left without a meaningful choice?

Decentralizing property is one way to restore balance to an unequal society.”

Now imagine that they built a fence around an area and told you that the “state” or “private security agency” would kick you in the balls if you stepped into there, their reasoning being that there are opportunities within that they’d like to take advantage of. Maybe the fenced area contains the only arable land in the whole field. Clearly, you need access to the fenced area or you will starve (even hypothetical people need to eat!)

The main argument here is that there is nothing given about this hierarchy. It’s an arbitrary product of the social relationship that obtains between you, the other person, and the institution that sides with him. It’s strange to describe this arrangement as a “right.” How many “rights” do you know of that operate by excluding others from the opportunity to exercise their own? When an institution arbitrarily privileges the benefit of the few over the needs of the many, it creates an imbalance that does violence to the whole of society. Property is one such institution, and the way to restore balance to it is by decentralizing.

Is property in fact centralized? It is, by necessity. In most societies the government holds a monopoly on force and reserves the right to act as sole enforcer in property disputes. Without centralization it is unlikely that an ambulance or conga line could efficiently pass through multiple regions without friction.

The problem is that state power is not evenly distributed; it favors those who already have capital (assets), allowing them to accumulate more land and resources over time. This is why those who have found themselves on the receiving end of the state’s monopoly on force (sometimes for reasons wholly outside of their control, and sometimes for generations) are not only placed at an immediate disadvantage, they are embedded within a system that cements disadvantage in place indefinitely. To describe this as “equal opportunity,” is… maybe overselling it a bit?

If this sounds far-fetched, consider the case of the United Fruit Company. In the early- to mid- twentieth century, the United Fruit Company owned sizable tracts of land throughout Latin America, which gave them huge influence over the local governments. By centralizing ownership of the land and critical infrastructure, the UFCO was able to dominate local economies and coerce people into working on the same lands they had farmed for hundreds of years before the Boston-based company began importing bananas to the United States. When the people balked at this arrangement and went on strike, the UFCO was quick to appeal to state enforcers (as they did in the famous Banana Massacre in Colombia, and the Guatemalan coup of 1954.) All this over some profitable potassium.

Decentralizing property does not need to be some radical act. Some of the world’s most successful social democracies already practice some form of property decentralization. Freedom to Roam laws, also referred to as Right to Roam laws, also referred to as Pure Weakling Entitlements (I made that last one up), are prevalent in the Nordic countries and surrounding regions. For private property deemed too vast, or limiting the public from experiencing beautiful regions considered socially desirable, they can be partially accessed used by the public, exercised on, hiked on, cried on (my specialty) etc. This is a compromise that maintains the property rights of landowners without eliminating opportunities for the public to use that land.

Intellectual property is another area ripe for decentralization. One way to keep the benefits of exclusion and simultaneously limit the enclosure of thought would be to limit the term of patents, implement a company-size tier for copyright — i.e larger companies have a harder time exercising intellectual property, etc. The goal here, again, is decentralization and dispersal of power.

There are many other ways we could effectively redistribute private property without going full-Bolshevik. In the United States, the tax code could be streamlined in a number of ways. A more progressive tax, such as this country had during the New Deal, would simply tax those with higher incomes at a higher rate than those with lower incomes, redistributing resources from the propertied to the dispossessed. An increased of the marginal tax rate on capital gains (i.e any income you could unknowingly earn while being in a coma) or inheritance (money income earned when its owner is no longer in a coma) would both be ways of making non-productive resources available to a greater number of people, and would sustain larger, more resilient markets from the ground up.

The concept of Employer of Last Resort (also called a Jobs Guarantee) is the basic idea that everyone in society who is able to work should be given the opportunity to do so. One of the contradictions of a system in which property is highly centralized is the requirement that everyone spend so much energy and resources acquiring property can leave many important tasks un-done. Unused resources, fallow land, capital kept out of circulation, underutilized labor could all be marshaled for the public benefit. If a sovereign government demands taxes in a currency it issues, then here it provides a means for everyone to earn that currency.

UBI, or Universal Basic Income. UBI is simple, is another policy proposal that is gaining traction from all across the political spectrum. The idea is simple in principle — just give everyone money. This is perhaps the most straightforward way of decentralizing wealth (and its attendant power); every person gets a set amount of money to spend however they see fit. A major benefit of UBI would be to liberate workers from the coercion they experience as a result of not owning property.

As Noam Chomsky once said in a 1996 Harvard speech on real world capitalism, critiquing the attitudes of some of its most powerful participants, “free markets are fine for you, but not for me.” Ultimately decentralizing property would lead to greater competition among those with capital, at the benefit of reduced competition for the rest of us.

Comments