Hurricanes Reveal a Fragile Infrastructure

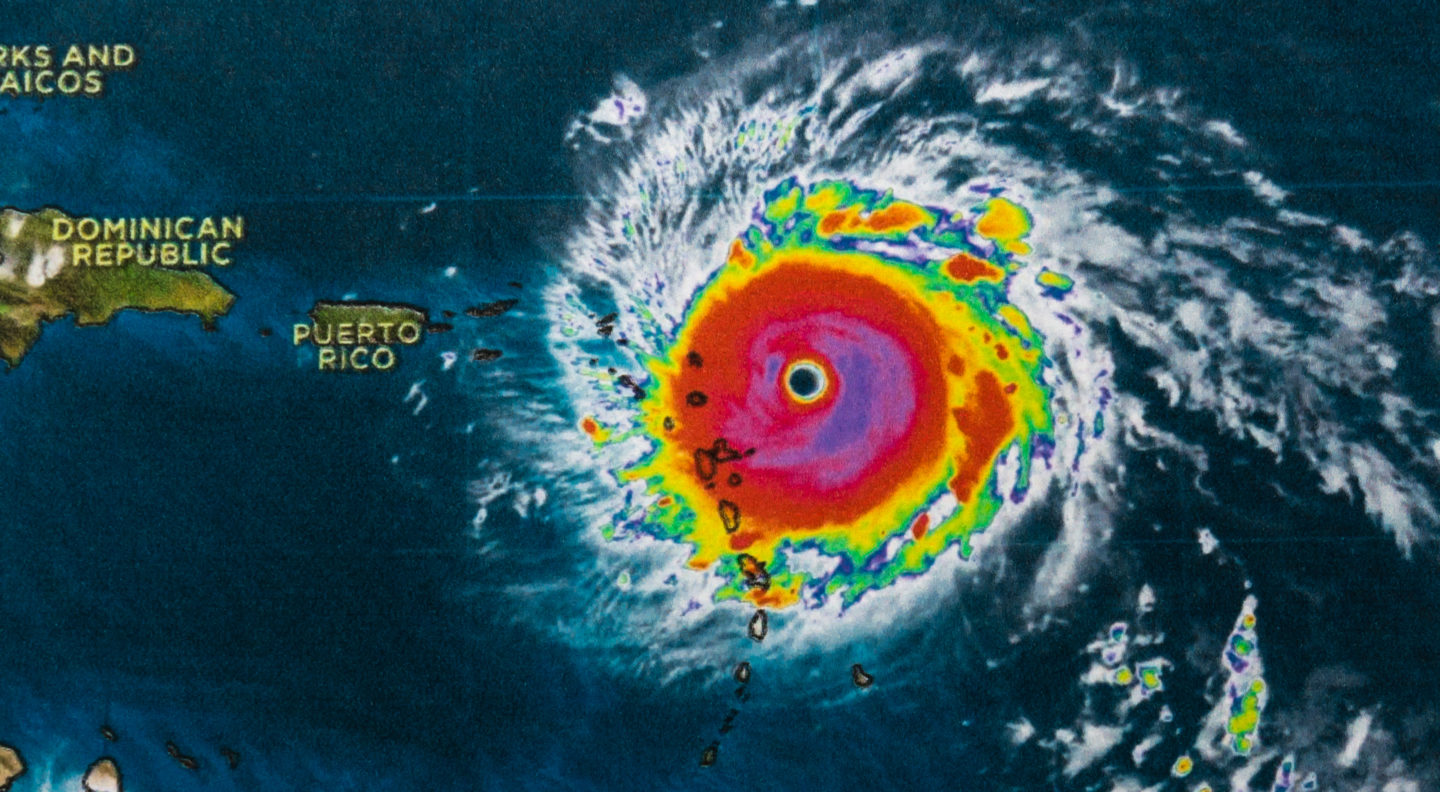

Last year’s hurricane season was brutal. 2017 hit the United States with four major hurricanes: Jose, Harvey, Irma, and Maria. These storms caused catastrophic flooding in Houston, took out nearly half of the cell sites in southwest Florida, devastated Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure for weeks, and wrought havoc everywhere they made landfall. The hurricane season […]

Last year’s hurricane season was brutal. 2017 hit the United States with four major hurricanes: Jose, Harvey, Irma, and Maria. These storms caused catastrophic flooding in Houston, took out nearly half of the cell sites in southwest Florida, devastated Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure for weeks, and wrought havoc everywhere they made landfall. The hurricane season of 2017 resulted in over one hundred deaths and caused more than $200 billion in damages, making it the second costliest hurricane season in U.S. history.

Storm forecasters do not anticipate 2018’s hurricane season to be as intense as last year’s, but predict that Atlantic hurricane activity will likely be above average. Some believe hurricanes are likely to become more frequent and severe in the near future, and warn that we should brace for more destructive storms, and more of them.

Even more distressing than the possibility of increasingly intense hurricanes is the fragility of the infrastructure in place to protect against them. The American Society for Civil Engineers gives the country’s infrastructure a ‘D+’ grade – somewhere between “mediocre, requires attention” and “poor, at risk.”

The infrastructural situation is especially dire in Puerto Rico. Irma and Maria left 95% of the island’s residents without power for days. (At the time of writing, some 30,000 people are still waiting for the electrical grid to come back online.) This is partially the result of an overly-centralized power system that depends on a few large oil-burning generators to power the whole grid. “When one fails: poof,” reports Adam Rogers in Wired.

“The engineering of our cities and urban areas are quite rigid and not flexible enough to handle and recover from natural disasters easily,” said Newsha Ajami, Senior Research Engineer at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

Houston is a perfect example of this point. In the last 30 years the city has grown by 35 percent, adding over half a million new residents since 1990. All of those people need somewhere to live, and before long Houston was building more new housing than anywhere else in the country. Rapid, unchecked development paved over many of the area’s wetlands and prairies, which would otherwise provide drainage and act as “sponges” to soak up some of the floodwaters and help mitigate storm damage. By eliminating natural flood barriers (and in some cases even constructing neighborhoods in FEMA-designated floodplains), Houston inadvertently built itself into a perfect flood.

In the event of any natural disaster it is crucially important to locate people and coordinate aid efforts. Unfortunately, hurricanes often destroy the critical communications infrastructure that makes these efforts possible. Harvey knocked out out 95 percent of cell sites in Aransas County, Texas, where it first touched down. In Puerto Rico, the one-two punch of Irma and Maria left 91 percent of the island without cell coverage. Family members in the mainland United States were unable to make contact with their loved ones in Puerto Rico for weeks after the storm.

The United Nations Office for disaster Risk Reduction has developed a metric against which cities can measure their resilience to disasters ranging from floods and hurricanes to climate change and social unrest. It’s a helpful rubric, but it also shows just how difficult it is for places already battered by disaster to recover. Faced with the immediate task of rebuilding damaged property, they are unable to mount the financial and logistical resources needed to make infrastructure repairs that could help prevent future damage. It’s easy to see how communities affected by hurricanes can get caught in a loop, reacting to the most recent disaster instead of preparing for the storms to come.

While building more resilient infrastructure is possible, the scale and complexity of the problem is certainly daunting. It would be difficult for a single agency solving the whole thing, but resiliency can come in many forms — from innovative new ideas in municipal development policy to community initiatives to build bioswales in local neighborhoods. It might take the resources of a large organization to harden the electricity grid or keep communications networks up during a disaster, but new technologies can help communities generate their own power or build people-powered networks.

Hurricane season starts on the first day of June.

Last year’s hurricane season was brutal. 2017 hit the United States with four major hurricanes: Jose, Harvey, Irma, and Maria. These storms caused catastrophic flooding in Houston, took out nearly half of the cell sites in southwest Florida, devastated Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure for weeks, and wrought havoc everywhere they made landfall. The hurricane season of 2017 resulted in over one hundred deaths and caused more than $200 billion in damages, making it the second costliest hurricane season in U.S. history.

Storm forecasters do not anticipate 2018’s hurricane season to be as intense as last year’s, but they do predict that Atlantic hurricane activity will likely be above average. Some believe hurricanes are likely to become more frequent and severe in the near future, and warn that we should brace for more destructive storms, and more of them.

Even more distressing than the possibility of increasingly intense hurricanes is the fragility of the infrastructure in place to protect against them. The American Society for Civil Engineers gives the country’s infrastructure a ‘D+’ grade – somewhere between “mediocre, requires attention” and “poor, at risk.”

The infrastructural situation is especially dire in Puerto Rico. Irma and Maria left 95% of the island’s residents without power for days. (At the time of writing, some 30,000 people are still waiting for the electrical grid to come back online.) This is partially the result of an overly-centralized power system that depends on a few large oil-burning generators to power the whole grid. “When one fails: poof,” reports Adam Rogers in Wired.

“The engineering of our cities and urban areas are quite rigid and not flexible enough to handle and recover from natural disasters easily,” said Newsha Ajami, Senior Research Engineer at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment.

The example of Houston is a case in point. In the last 30 years the city has grown by 35 percent, adding over half a million new residents since 1990. In order to meet the growing demand for housing, Houston began building more new residences than anywhere else in the country. Rapid, unchecked development paved over many of the area’s wetlands and prairies, which would otherwise provide drainage and act as “sponges” to soak up some of the floodwaters and help mitigate storm damage. By eliminating natural flood barriers (and in some cases even constructing neighborhoods in FEMA-designated floodplains), Houston inadvertently built itself into a perfect flood.

In the event of any natural disaster it is crucially important to be able to locate people and coordinate aid efforts. Unfortunately, hurricanes often destroy the communications infrastructure that makes these efforts possible. Harvey knocked out out 95 percent of cell sites in Aransas County, Texas, where it first touched down. In Puerto Rico, the one-two punch of Irma and Maria left 91 percent of the island without cell coverage. Family members in the mainland United States were unable to make contact with their loved ones in Puerto Rico for weeks after the storm.

The United Nations Office for disaster Risk Reduction has developed a metric against which cities can measure their resilience to disasters ranging from floods and hurricanes to climate change and social unrest. It’s a helpful rubric, but it also shows just how difficult it is for places already battered by disaster to recover. Faced with the immediate task of rebuilding damaged property, they are unable to mount the financial and logistical resources needed to make infrastructure repairs that could help prevent future damage. It’s easy to see how communities affected by hurricanes can get caught in a loop, reacting to the most recent disaster instead of preparing for the storms to come.

While building more resilient infrastructure is possible, the scale and complexity of the problem is certainly daunting. It would be difficult for a single agency solving the whole thing, but resiliency can come in many forms — from innovative new ideas in municipal development policy to community initiatives to build bioswales in local neighborhoods. It might take the resources of a large organization to harden the electricity grid or keep communications networks up during a disaster, but new technologies can help communities generate their own power or build people-powered networks.

Hurricane season officially begins the first day of June.

Comments