11 Reasons Your Personal Data Is Actually Poetry

1) I would like to draw your attention to the list.

“We feel better when the amount of conscious work we have to do to process something is reduced” writes Maria Konnikova in The New Yorker. “A list… promises a definite ending: we think we know what we’re in for, and the certainty is both alluring and reassuring.”

2) You do not, in fact, “know what you are in for.”

“Isn’t this about data?” you are asking. “The headline said it was about data.”

3) Lists are very old.

List-making is older than any other any other form of writing. There are artifacts

dating from tens of thousands of years before any formal writing system was developed, which archaeologists believe are records that early farmers kept of how many sheep and goats they had in their flocks.

One of the earliest extant pieces of writing is The Instructions of Shuruppak, which dates from the third millennium BCE (for context, that is two thousand years before the list of the descendants of Adam appeared in the book of Genesis). Most of this ancient Sumerian tablet is taken up by lengthy list of Bronze Age truisms (“You should not buy a donkey which brays… you should not make a well in your field… you should not commit robbery; you should not cut yourself with an axe…”)

As civilizations developed concepts of lineage, agriculture, commerce, governments, and libraries, it became more and more important to record more and more information. Hence, more and more lists.

4) Lists make us feel in control.

As many a self-help listicle advises, when you are feeling disorganized, overwhelmed, or demotivated, one of the first things you should do is make a list. By naming all of your problems, you make them present and actionable.

5) Lists are a form of poetry.

Bards and singers in oral poetic traditions used lists to help them remember long epic poems, which is why lists in written poetry are also called “epic catalogues.” Epic catalogues feature in the works of Homer, Virgil, Rabelais, Spenser (skip to xiii), Milton, Whitman, and many, many more.

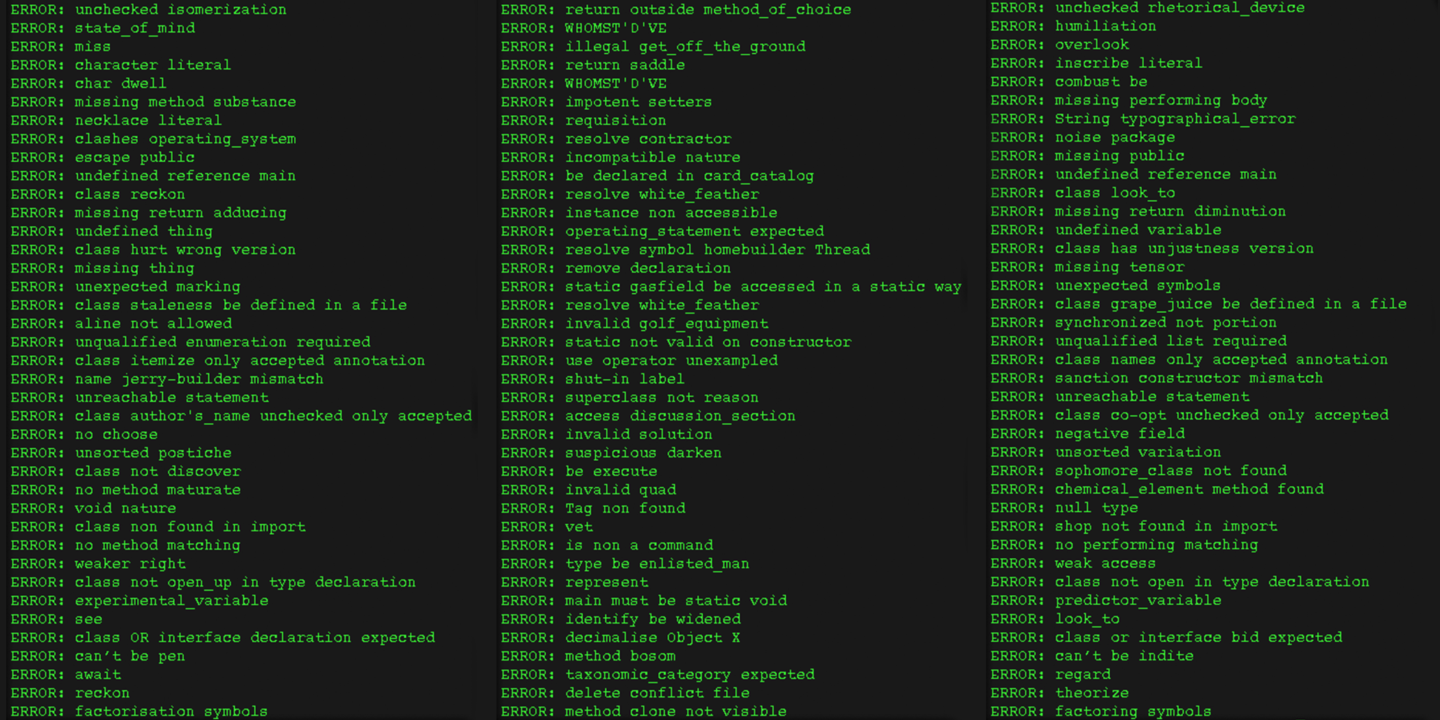

6) A database is a digital list.

Today we make digital lists (also known as databases) on a scale that would have made

Sumerian goat herders weep in awe and horror. Our:

- social security numbers

- our financial information

- our browsing history

- our communications with other people

- the identities of our friends, families, and loose acquaintances

- our shoe sizes

- favorite brand of toothpaste

- preferred types of porn

- our political affiliations

- our hobbies

- the music we like

- the food we order on Seamless,

- our Amazon wishlists

- etc.

are all stored in a cells in spreadsheets in databases on servers somewhere far, far away.

By simply going about your life, you have been producing catalogues of epic proportions. Amidst government surveillance and private data mining operations, you have been writing lists — a little indirectly — for years.

7) Databases are decentralized poetry.

If all lists can be poetry, and all databases are lists, then all databases can be poetry.

But these poems have no precise beginning or end, no single author. They are distributed around the world. They are decentralized!

8) You are writing the poem, so they belong to you.

Databases lists are populated as a result of actions that you are taking — sometimes even literal keystrokes from your fingers. And if it’s a poem that you’ve written yourself, then you own the IP.

9) But you can’t read it.

The way things are right now, you will be able to read this poem precisely never.

10) You do not, in fact, “know what you are in for.”

The data sequestered away in on all of those cells in spreadsheets in databases on servers far, far away will be used to determine an increasingly significant part of your life. But if you don’t have access to it, you can’t verify whether or not it is metrically sound, assonant — never mind accurate.

11) We are close to having a system in which people own their data.

Under the current model anybody can have access to your data as long as they can either collect it or pay for it. It’s like someone reading through your journal looking for information that might be useful to them in the future.

But there is another way. If data transactions were carried out on the blockchain, as some have suggested, other parties would have to pay you for your data.If you didn’t want to give them access to your personal information, you could raise the price, or refuse to sell.

1) I would like to draw your attention to the list.

“We feel better when the amount of conscious work we have to do to process something is reduced” writes Maria Konnikova in The New Yorker. “A list… promises a definite ending: we think we know what we’re in for, and the certainty is both alluring and reassuring.”

2) You do not, in fact, “know what you are in for.”

“Isn’t this about data?” you are asking. “The headline said it was about data.”

3) Lists are very old.

List-making is older than any other any other form of writing. There are artifacts dating from tens of thousands of years before any formal writing system was developed, which archaeologists believe are records that early farmers kept of how many sheep and goats they had in their flocks.

One of the earliest extant pieces of writing is The Instructions of Shuruppak, which dates from the third millennium BCE (for context, that is two thousand years before the list of the descendants of Adam appeared in the book of Genesis). Most of this ancient Sumerian tablet is taken up by lengthy list of Bronze Age truisms (“You should not buy a donkey which brays… you should not make a well in your field… you should not commit robbery; you should not cut yourself with an axe…”)

As civilizations developed concepts of lineage, agriculture, commerce, governments, and libraries, it became more and more important to record more and more information. Hence, more and more lists.

4) Lists make us feel in control.

As many a self-help listicle advises, when you are feeling disorganized, overwhelmed, or demotivated, one of the first things you should do is make a list. By naming all of your problems, you make them present and actionable.

5) Lists are a form of poetry.

Bards and singers in oral poetic traditions used lists to help them remember long epic poems, which is why lists in written poetry are also called “epic catalogues.” Epic catalogues feature in the works of Homer, Virgil, Rabelais, Spenser (skip to xiii), Milton, Whitman, and many, many more.

6) A database is a digital list.

Today we make digital lists (also known as databases) on a scale that would have made Sumerian goat herders weep in awe and horror. Our:

- social security numbers

- our financial information

- our browsing history

- our communications with other people

- the identities of our friends, families, and loose acquaintances

- our shoe sizes

- favorite brand of toothpaste

- preferred types of porn

- our political affiliations

- our hobbies

- the music we like

- the food we order on Seamless,

- our Amazon wishlists

- etc.

are all stored in a cells in spreadsheets in databases on servers somewhere far, far away.

By simply going about your life, you have been producing catalogues of epic proportions. Amidst government surveillance and private data mining operations, you have been writing lists — a little indirectly — for years.

7) Databases are decentralized poetry.

If all lists can be poetry, and all databases are lists, then all databases can be poetry.

But these poems have no precise beginning or end, no single author. They are distributed around the world. They are decentralized!

8) You are writing the poem, so they belong to you.

Databases lists are populated as a result of actions that you are taking — sometimes even literal keystrokes from your fingers. And if it’s a poem that you’ve written yourself, then you own the IP.

9) But you can’t read it.

The way things are right now, you will be able to read this poem precisely never.

10) You do not, in fact, “know what you are in for.”

The data sequestered away in on all of those cells in spreadsheets in databases on servers far, far away will be used to determine an increasingly significant part of your life. But if you don’t have access to it, you can’t verify whether or not it is metrically sound, assonant — never mind accurate.

11) We are close to having a system in which people own their data.

Under the current model anybody can have access to your data as long as they can either collect it or pay for it. It’s like someone reading through your journal looking for information that might be useful to them in the future.

But there is another way. If data transactions were carried out on the blockchain, as some have suggested, other parties would have to pay you for your data.If you didn’t want to give them access to your personal information, you could raise the price, or refuse to sell.

You could be as arbitrary or artful with your data as a poet is with their words. The record of every transaction would be posted to a public ledger — the most epic catalogue imaginable at present — so there would be always be a decentralized audience to verify that every poem is paid for.

Comments