Frontier Mars: An Interview with Michael Solana

The Mars of myth was both a god of war and a protector of agriculture — a potent pairing in the agrarian military society of imperial Rome. Although almost no one believes in Mars anymore, the planet bearing his name invokes the same strong feelings the ancient god used to stand for: energy, desire, the […]

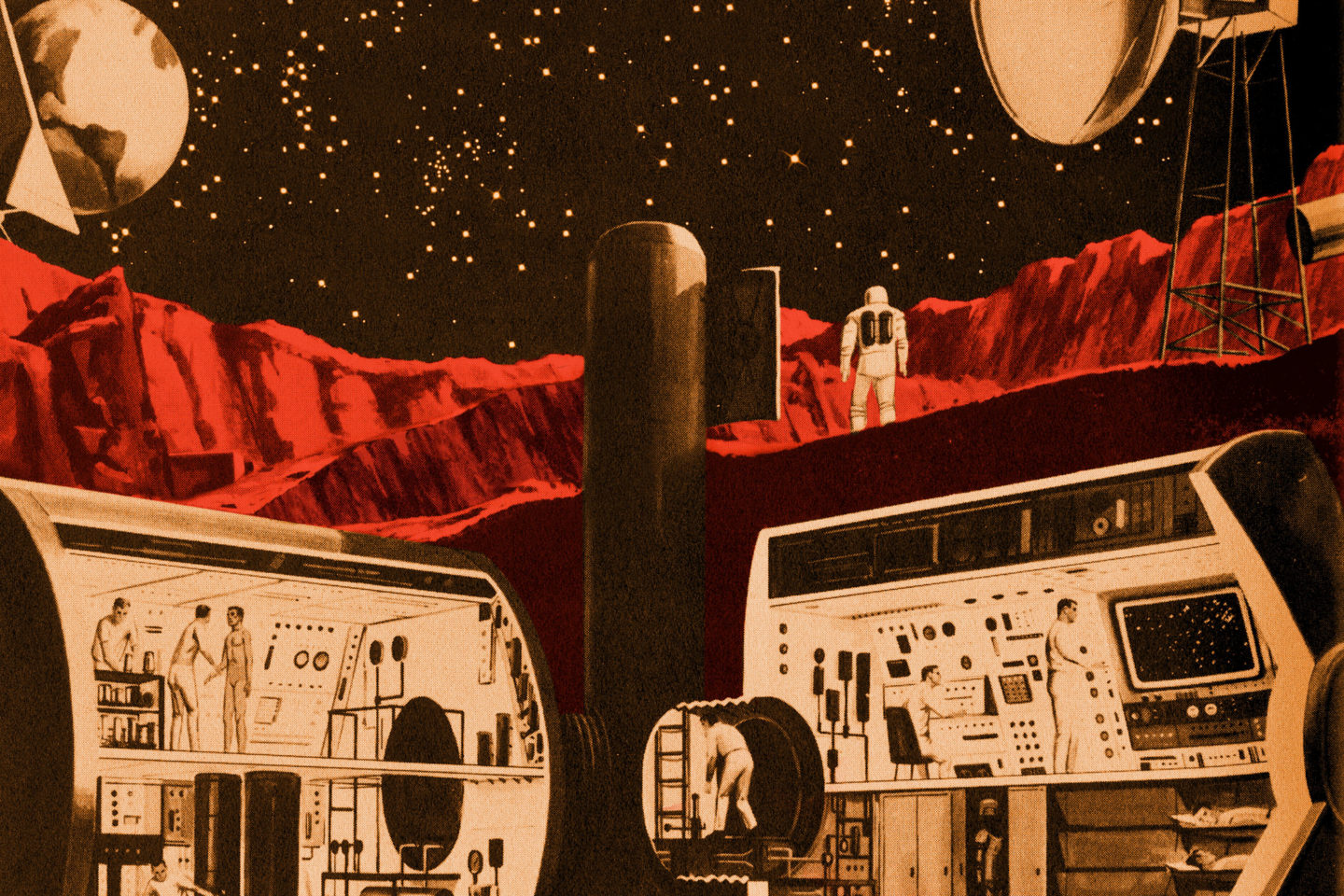

The Mars of myth was both a god of war and a protector of agriculture — a potent pairing in the agrarian military society of imperial Rome. Although almost no one believes in Mars anymore, the planet bearing his name invokes the same strong feelings the ancient god used to stand for: energy, desire, the irrepressible drive to dominate and survive. A growing number of scientists, engineers and future-oriented entrepreneurs see going to Mars as the “next giant leap” for mankind, an opportunity to turbocharge innovation and reinvigorate technological progress. Some have suggested the technology we will need to develop to settle Mars will be able to address some of Earth’s mounting ecological problems. Elon Musk, one of the most prominent avatars of the Mars movement, has even described Mars as a “backup drive” for humanity, (in the event that it doesn’t work out so well Earth, presumably).

Michael Solana writes, produces, and hosts the Anatomy of Next podcast for the Founders Fund, a San Francisco venture capital firm where he is also a vice president. To say that he is enthusiastic about Mars is a pretty dramatic understatement. “It’s the only way our species survives,” he tells me on the phone. Solana has dedicated the second season of his podcast to investigating Mars — why we should go, how we will get there, and what we will do once we land.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Eamon O’Connor : Why we should devote money and resources going to Mars? Don’t we have more pressing problems to solve here on Earth?

Michael Solana: This is the question I get most often – more than “Why haven’t we done this yet?” or “Is this possible?” even. I’ve always found the answer almost self-evident: if you care about people — if you’re a humanist, and you care about solving problems that affect people — Mars is the path. Mars is a forcing function. To create a new world, we have to reimagine what we’re doing on Earth, and so by building a new model, we reinvigorate the old system.

The question “why Mars over Earth” seems to stem from an impulse to frame this whole endeavor as a choice: solving local, tangible problems or throwing money at a pipe dream. But what problems are we working on solving today that we would stop working on once we start seriously working on Mars? Elon [Musk] is already building rocket ships that land, and he’s working on dramatically reducing the cost of launch. Have we seen a decline in funding for cancer research, or infrastructural development, or a rise in hunger or poverty because of it? Of course not. This is just immediately a very strange, and I think fallacious frame.

The real question is: what’s happening in these spaces now? Because I do think the naysayers are onto something, they’re just projecting our current reality into the future. It seems progress has slowed. Certainly our willingness to adopt technology has slowed, and I think this is because in order to address any one of these quite enormous problems, you have to totally scrap a pre-existing system that affects hundreds of millions, or in some cases billions of people. And people hate change.

Mars is the path. Mars is a forcing function. By building a new model, we reinvigorate the old system.”

At their core, as the stuff of civilization is currently ordered, infrastructural problems are almost all political problems. No one is voting in the guy who wants to delete the entire healthcare system and start over with something that’s never been done before. But starting over is the only way to make use of everything we’ve learned these past few hundred years, and to properly implement all of the technology we’ve developed. Now, there is a place, historically, that has been ripe for trying new things out, and building new infrastructural systems. We call it the frontier, and today we don’t have one.

Humans tend to operate with something called a status quo bias – an emotional preference for whatever already exists, no matter its quality. Changing a thing that works, however so imperfectly, is almost impossible at the scale of ‘all civilization.’ As I wrote in a recent essay, “in new places new things are necessarily built, and when they work they proliferate. It was America, our first new world, where the skyscraper came alive before scaling globally. It’s no coincidence modern computing was invented on this nation’s west coast, at the continent’s extreme opposite of the first European settlements, nor is it a coincidence so much of our modern programming was invented online, collaboratively, on our first digital frontier.”

We need to build new things on Mars because it is actually possible to build new things on Mars.

EO: Who will the first people to settle Mars? What will they bring with them?

MS: So Mars is actually worse than Mad Max: a brutal, freezing, rust-covered, super-radiated desert world with a razor thin atmosphere and no readily-accessible water. It is totally lethal to every form of life we currently know. The kind of people looking to settle a world like that – not just explore, but colonize at that early state – are probably gonna be a little crazy. Frontiersmen always are. You almost have to be, because at one of the most – if not the most – comfortable moments in human civilization for highly-capable people, you’re signing up for a hard life.

But Mars also has a day roughly comparable to Earth’s, and seasons. Mars has a decent amount of gravity. Mars has probably every element we need to grow organics. And so Mars, despite being a brutal world for life today, has an extraordinary potential. We can make Mars into something a lot like Earth, which means if you’re heading off to colonize, in addition to signing up for a hard life, you’re also making history. You’re also potentially saving humankind. So I do think the early colonizers will wind up being a very, very idealistic crew.

In terms of what they bring – the very first explorers will need to take almost everything they need to live for the shorter term along with them, in addition to pieces of what they’ll need to build sustainability into the new world for the longer term. With each new group of folks who arrive on Mars, there will be more stuff to work with: solar cells, nuclear reactors, various bacteria cultures, tools for genetic experiments, design, and manufacturing, and a whole host of weird robots. As the years go on, we’ll build infrastructure into the new world: energy, water, food production, waste management. And slowly, we’ll terraform the planet.

EO: What kind of society do you imagine the early settlers will form?

MS: In terms of the society that emerges, I of course can’t know that for sure. But I imagine it will be something like an intellectual monoculture at first. There will likely be significant diversity in terms of say, race, gender, sexuality, what have you – but almost no diversity on values. People will be there because they believe humans are good, that our survival, and the preservation of life, is important. They’ll believe change is good – and changing nature, to some extent, is good. They’ll also have to be physically tough in order to survive, and intellectually capable, as they’ll have to be extraordinary problem solvers. Longer term, I don’t know what a family of people like that turns into. The closest historical parallel we have is in the story of the Americas, but it’s not quite right; in America, there were abundant resources. In Mars, we’re making blood from stone – literally.

We need to build new things on Mars because it is actually possible to build new things on Mars.”

EO: Many people have intense emotional responses when the topic of Mars comes up. What do you think accounts for this?

MS: I definitely agree. When I talk about Mars, I’m either greeted with blind, optimistic cheer, or what almost seems like anger. Both reactions are concerning.

The blind optimism is concerning because blind optimism doesn’t move the dial – we need a plan to get to Mars, and resources dedicated to the task, or it’s never going to happen. The anger is concerning because, philosophically, I think there’s an existential issue here: Mars represents, in a very lush, well-defined way, a future for the human race that is bigger than Earth.

It’s very reasonable to want to participate in this. If people were angry because they felt excluded, I would be less concerned. But increasingly it seems people are angry about Mars at the conceptual level, and to me this is a philosophical tell, an admission of an anti-human motive lodged somewhere in the concerned parties’ value systems.

In “The Matrix”, Agent Smith says people are a virus. This is quoted to me all the time, and it’s always framed as some kind of true, edgy position. But it’s horrifying – and spouting off the platitudes that dominate our intellectual culture is never edgy. On that quote, it’s important to remember the villain of the movie says this. The guy who wants to destroy the human race says this, while torturing Morpheus, the guy who wants to save us.

To anyone who casually believes we are a virus, you need to remember you are a part of this race. You are a part of this group you find destructive at its core. So are you talking about yourself? Do you really not believe you deserve to live? This is the philosophy of a future suicide victim, and daily I am more convinced it’s driving our civilization to extinction, starting with a kind of intellectual suicide – the swearing off of human concerns, and of a belief in human potential.

Mars is the corrective to [this] anti-human thinking. So this is why I do what I do. I don’t believe colonizing Mars is one, beautiful thing our species is capable of. I believe if we don’t do it we end.

EO: In your recent essay (referenced above) you write “Trust in the technology industry seems to be waning, and this waning trust is not entirely unjustified.” Is a general mistrust of the technology industry driving the recently-more negative outlook on Mars?

MS: First, I really don’t think the negative outlook on Mars is the consensus, or even dominant sentiment. While many people are beginning to look towards the future, in general, more skeptically, I think Mars is still something most people agree is important.

This isn’t like artificial intelligence, which really seems to frighten most people. Mars feels more like an antidote to the indeterminate pessimism now gripping our academics, our media, and increasingly the broader public. So the recent uptick in skepticism, and even anger directed toward the Martian question is alarming, and I believe proliferation of these feelings will cripple our ability to progress.

Now, on the nature of this vocal minority – It’s always hard to say what specifically is driving a social phenomenon, and I need to caveat with an admission there’s of course no real data, here, so I really only have my gut. But the arguments against Mars from the early 90s focused largely on technical and budgetary skepticism. Today dissent is largely coming from a philosophical or political-philosophical place. Mistrust of the technology industry is a part of this.

But skeptics also come at Mars with a class argument. People have asked me about the gender and racial diversity of Mars. People increasingly come at this on very abstract ethical grounds – if there is some form of alien life native to Mars, might our presence harm it? And even if Mars is barren, what gives us the right to change it? What gives us the right to change anything? The natural environment is perfect as it is – almost, you might say, sacred. To me, this seems to come from a religious place, and a kind of worshipping of Mother Nature.

I think the weirder thing that may be happening is more intelligent people are increasingly suspicious we’re going to Mars at all. Float that idea on Twitter – it’s not popular. So maybe all of these very nebulous, half-sketched social arguments, ethical arguments, religious arguments – is how we get away from voicing the scariest criticism of the Martian endeavor of all: our leaders may not be capable of pulling it off.

The Mars of myth was both a god of war and a protector of agriculture — a potent pairing in ancient Rome, where the only thing more important than the military was growing enough food to feed the imperial army. Although almost no one believes in Mars anymore, the planet bearing his name still invokes the same strong feelings the ancient god used to stand for: energy, desire, the irrepressible drive to dominate and survive. A growing number of scientists and future-oriented entrepreneurs see going to Mars as the “next giant leap” for mankind, an opportunity to turbocharge innovation and reinvigorate technological progress. Some have suggested the technology we will need to develop to settle Mars will be able to address some of Earth’s mounting ecological problems. Elon Musk, one of the most prominent avatars of the Mars movement, has even described Mars as a “backup drive” for humanity, (in the event that it doesn’t work out so well on Earth, presumably).

Michael Solana writes, produces, and hosts the Anatomy of Next podcast for the Founders Fund, a San Francisco venture capital firm where he is also a vice president. To say that he is enthusiastic about Mars is a pretty dramatic understatement. “It’s the only way our species survives,” he tells me on the phone. Solana has dedicated the second season of his podcast to investigating Mars — why we should go, how we will get there, and what we will do once we land.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Eamon O’Connor : Why we should devote money and resources going to Mars? Don’t we have more pressing problems to solve here on Earth?

Michael Solana: This is the question I get most often – more than “Why haven’t we done this yet?” or “Is this possible?” even. I’ve always found the answer almost self-evident: if you care about people — if you’re a humanist, and you care about solving problems that affect people — Mars is the path. Mars is a forcing function. To create a new world, we have to reimagine what we’re doing on Earth, and so by building a new model, we reinvigorate the old system.

The question “Why Mars over Earth?” seems to stem from an impulse to frame this whole endeavor as a choice: solving local, tangible problems or throwing money at a pipe dream. But what problems are we working on solving today that we would stop working on once we start seriously working on Mars? Elon [Musk] is already building rocket ships that land, and he’s working on dramatically reducing the cost of launch. Have we seen a decline in funding for cancer research, or infrastructural development, or a rise in hunger or poverty because of it? Of course not. This is just immediately a very strange, and I think, fallacious frame.

The real question is: what’s happening in these spaces now? Because I do think the naysayers are onto something, they’re just projecting our current reality into the future. It seems progress has slowed. Certainly our willingness to adopt technology has slowed, and I think this is because in order to address any one of these quite enormous problems, you have to totally scrap a pre-existing system that affects hundreds of millions, or in some cases billions of people. And people hate change.

Mars is the path. Mars is a forcing function. By building a new model, we reinvigorate the old system.”

At their core, as the stuff of civilization is currently ordered, infrastructural problems are almost all political problems. No one is voting in the guy who wants to delete the entire healthcare system and start over with something that’s never been done before. But starting over is the only way to make use of everything we’ve learned these past few hundred years, and to properly implement all of the technology we’ve developed. Now, there is a place, historically, that has been ripe for trying new things out, and building new infrastructural systems. We call it the frontier, and today we don’t have one.

Humans tend to operate with something called a status quo bias – an emotional preference for whatever already exists, no matter its quality. Changing a thing that works, however so imperfectly, is almost impossible at the scale of ‘all civilization.’ As I wrote in a recent essay, “in new places new things are necessarily built, and when they work they proliferate. It was America, our first new world, where the skyscraper came alive before scaling globally. It’s no coincidence modern computing was invented on this nation’s west coast, at the continent’s extreme opposite of the first European settlements, nor is it a coincidence so much of our modern programming was invented online, collaboratively, on our first digital frontier.”

We need to build new things on Mars because it is actually possible to build new things on Mars.

EO: Who will be the first people to settle Mars? What will they bring with them?

MS: So Mars is actually worse than Mad Max: a brutal, freezing, rust-covered, super-radiated desert world with a razor thin atmosphere and no readily-accessible water. It is totally lethal to every form of life we currently know. The kind of people looking to settle a world like that – not just explore, but colonize at that early state – are probably gonna be a little crazy. Frontiersmen always are. You almost have to be, because at one of the most – if not the most – comfortable moments in human civilization for highly-capable people, you’re signing up for a hard life.

But Mars also has a day roughly comparable to Earth’s, and seasons. Mars has a decent amount of gravity. Mars has probably every element we need to grow organics. And so Mars, despite being a brutal world for life today, has an extraordinary potential. We can make Mars into something a lot like Earth, which means if you’re heading off to colonize, in addition to signing up for a hard life, you’re also making history. You’re also potentially saving humankind. So I do think the early colonizers will wind up being a very, very idealistic crew.

In terms of what they bring – the very first explorers will need to take almost everything they need to live for the shorter term along with them, in addition to pieces of what they’ll need to build sustainability into the new world for the longer term. With each new group of folks who arrive on Mars, there will be more stuff to work with: solar cells, nuclear reactors, various bacteria cultures, tools for genetic experiments, design, and manufacturing, and a whole host of weird robots. As the years go on, we’ll build infrastructure into the new world: energy, water, food production, waste management. And slowly, we’ll terraform the planet.

EO: What kind of society do you imagine the early settlers will form?

MS: In terms of the society that emerges, I of course can’t know that for sure. But I imagine it will be something like an intellectual monoculture at first. There will likely be significant diversity in terms of say, race, gender, sexuality, what have you – but almost no diversity on values. People will be there because they believe humans are good, that our survival, and the preservation of life, is important. They’ll believe change is good – and changing nature, to some extent, is good. They’ll also have to be physically tough in order to survive, and intellectually capable, as they’ll have to be extraordinary problem solvers. Longer term, I don’t know what a family of people like that turns into. The closest historical parallel we have is in the story of the Americas, but it’s not quite right; in America, there were abundant resources. In Mars, we’re making blood from stone – literally.

We need to build new things on Mars because it is actually possible to build new things on Mars.”

EO: Many people have intense emotional responses when the topic of Mars comes up. What do you think accounts for this?

MS: I definitely agree. When I talk about Mars, I’m either greeted with blind, optimistic cheer, or what almost seems like anger. Both reactions are concerning.

The blind optimism is concerning because blind optimism doesn’t move the dial – we need a plan to get to Mars, and resources dedicated to the task, or it’s never going to happen. The anger is concerning because, philosophically, I think there’s an existential issue here: Mars represents, in a very lush, well-defined way, a future for the human race that is bigger than Earth.

It’s very reasonable to want to participate in this. If people were angry because they felt excluded, I would be less concerned. But increasingly it seems people are angry about Mars at the conceptual level, and to me this is a philosophical tell, an admission of an anti-human motive lodged somewhere in the concerned parties’ value systems.

In “The Matrix”, Agent Smith says people are a virus. This is quoted to me all the time, and it’s always framed as some kind of true, edgy position. But it’s horrifying – and spouting off the platitudes that dominate our intellectual culture is never edgy. On that quote, it’s important to remember the villain of the movie says this. The guy who wants to destroy the human race says this, while torturing Morpheus, the guy who wants to save us.

To anyone who casually believes we are a virus, you need to remember you are a part of this race. You are a part of this group you find destructive at its core. So are you talking about yourself? Do you really not believe you deserve to live? This is the philosophy of a future suicide victim, and daily I am more convinced it’s driving our civilization to extinction, starting with a kind of intellectual suicide – the swearing off of human concerns, and of a belief in human potential.

Mars is the corrective to [this] anti-human thinking. So this is why I do what I do. I don’t believe colonizing Mars is one, beautiful thing our species is capable of. I believe if we don’t do it we end.

EO: In your recent essay (referenced above) you write “Trust in the technology industry seems to be waning, and this waning trust is not entirely unjustified.” Is a general mistrust of the technology industry driving the recently-more negative outlook on Mars?

MS: First, I really don’t think the negative outlook on Mars is the consensus, or even dominant sentiment. While many people are beginning to look towards the future, in general, more skeptically, I think Mars is still something most people agree is important.

This isn’t like artificial intelligence, which really seems to frighten most people. Mars feels more like an antidote to the indeterminate pessimism now gripping our academics, our media, and increasingly the broader public. So the recent uptick in skepticism, and even anger directed toward the Martian question is alarming, and I believe proliferation of these feelings will cripple our ability to progress.

Now, on the nature of this vocal minority – It’s always hard to say what specifically is driving a social phenomenon, and I need to caveat with an admission there’s of course no real data, here, so I really only have my gut. But the arguments against Mars from the early 90s focused largely on technical and budgetary skepticism. Today dissent is largely coming from a philosophical or political-philosophical place. Mistrust of the technology industry is a part of this.

But skeptics also come at Mars with a class argument. People have asked me about the gender and racial diversity of Mars. People increasingly come at this on very abstract ethical grounds – if there is some form of alien life native to Mars, might our presence harm it? And even if Mars is barren, what gives us the right to change it? What gives us the right to change anything? The natural environment is perfect as it is – almost, you might say, sacred. To me, this seems to come from a religious place, and a kind of worshipping of Mother Nature.

I think the weirder thing that may be happening is more intelligent people are increasingly suspicious we’re going to Mars at all. Float that idea on Twitter – it’s not popular. So maybe all of these very nebulous, half-sketched social arguments, ethical arguments, religious arguments – is how we get away from voicing the scariest criticism of the Martian endeavor of all: our leaders may not be capable of pulling it off.

Michael Solana is the creator/producer of Anatomy of Next, and a vice president at Founders Fund, a venture capital firm in San Francisco. He also writes stories about teenagers with superpowers. Follow him on Twitter @micsolana, and listen to Anatomy of Next here.

Comments